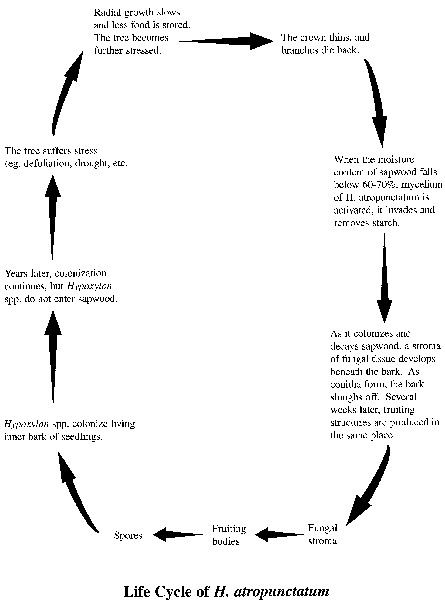

Hypoxylon canker is common throughout the South on oaks and other hardwoods where it normally occurs on stressed hosts. The canker is caused by one or more species of fungi in the genus Hypoxylon. Found in the outer bark areas of living and healthy trees, the fungi are normally of little consequence. However, Hypoxylon can severely injure or kill trees weakened by factors such as drought, root disease, mechanical injury, logging or construction activities. These agents of stress enable the fungus to move into the xylem and produce cankers on the branches and trunk. Apparently, the fungus is activated by reduced moisture in the xylem and bark. Once this low moisture threshold is reached, the fungi quickly spread. Especially in droughty areas, Hypoxylon fungi are often associated with tree death. Other fungi found in weakened trees may also play a role. In recent years more oaks have been dying across the South. In many cases, the affected trees are victims of oak decline, a complex of environmental stress, site factors, and living agents, of which Hypoxylon canker is a major contributor. Trees infected with Hypoxylon often develop severe injuries on the branches or trunk. They may also exhibit crown dieback. Large patches of bark of infected trees often slough off along the trunk and major branches revealing the fungus fruiting bodies (Figure 134). In spring or early summer, powdery greenish to brown or gray masses of the spores (conidia) are produced on the surface of crusty, fungal tissue patches (stromata). These stromata are the most obvious signs of Hypoxylon canker. They vary from less than ¼ inch to 3 feet long or more, running along the stem and main branches. In the summer or fall, these stromata thicken, harden, and turn silver or bluish-gray to brown or to black depending on the Hypoxylon species. Small slightly raised dots may be found on the surface of these masses. These are the tops of small chambers where a second type of spore (ascospore) is produced.

Hazard rating stands and trees- many species of oak (and to a lesser hickory) throughout the South are hosts to Hypoxylon canker. Trees growing on clay, sandy, rocky or other poor soils are highly susceptible to this disease, particularly during extended drought. Some of the most commonly affected oak species are post, southern red, white, water, and chestnut oak and blackjack. Nevertheless, all oak species are vulnerable under conditions favorable to the development of the fungi. Any condition that reduces vigor can predispose trees to Hypoxylon canker. Site and species factors also influence susceptibility. When put together these factors could show whether Hypoxylon canker may be likely to present problems in a given stand. Some of the more important factors to consider are:

What to do in forested areas? In forested areas, the key is prevention. Forest management practices such as thinning are very beneficial and increase tree vigor. However, improperly applied practices can actually worsen Hypoxylon infection through injury, exposure, and site changes. Basically, any forestry practice that increases stand vigor is encouraged. Conversely, any practice that stresses trees must be evaluated very carefully. Often, you must consider whether active stand management is likely to increase or decrease damage from Hypoxylon canker. It is advisable to delay stand disturbances during drought. When Hypoxylon canker is present in a forested stand evaluate it from the aspect of tree species and number of trees affected. If practical, salvage infected trees before they die. Proceed carefully, because the stress of logging may aggravate stand stresses. If removal of infected trees may result in an understocked stand, consider a final harvest cut. Then regenerate with species that are immune or resistant to Hypoxylon canker. An option for large forests is to set aside infected timber stands for other objectives such as wildlife. What to do in urban areas? - The key to Hypoxylon canker-free trees is prevention. Prevent injury to trees during construction (Figure 135). Avoid herbicide injury and minimize site changes.

|

||||||||

Forest Pests: Insects, Diseases & Other Damage Agents |

|

|