Fusarium Root RotDavid W. Johnson - Supervisory Plant Pathologist, Region 2, USDA Forest Service, Lakewood, CO, Cordell C.E., Anderson R.L., Hoffard W.H., Landis T.D., Smith R.S. Jr., Toko H.V., 1989. Forest Nursery Pests. USDA Forest Service, Agriculture Handbook No. 680, 184 pp. Hosts Fusarium root rot, caused by several species of Fusarium, including F. roseum, F. solani, and F. oxysporum, affects seedlings of most conifer species. Douglas-fir and pines are most susceptible to the disease; spruces are less susceptible; cypresses and cedars are relatively resistant. Distribution The disease is common throughout North America and in many other parts of the world. It especially has been a problem in westem Canada and the Western United States and in the North Central and Southern States. Damage Fusarium root rot causes seedling mortality in the nursery, increased numbers of culls, and reduced survival after outplanting. Mortality generally is confined to the first growing season. Losses vary greatly depending on tree species, seedlot, geographic area, and soil type.

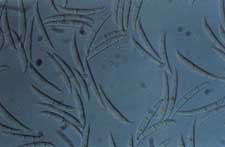

Diseased root systems have few laterals, and existing roots are often dark, swollen, and lack actively growing tips (fig. 7-2). Although the disease usually is fatal, it may sometimes destroy only the primary root, resulting in a deformed root system and stunted seedling (fig. 7-3). The bark and cortex can be stripped away easily from the cambium (fig. 7-4). Fusarium can be isolated from infected tissue on common laboratory media. In culture, the mycelium is extensive, often with a tinge of pink, purple, orange, or yellow (fig. 7-5), which is most discernible through the bottom of the culture plate. Conidiophores vary from slender to stout with irregular branches or a whorl of phialides, single or grouped into sporodochia. Conidia are colorless, often held in a gelatinous mass, and of two kinds: macroconidia, which are multicelled, slightly curved or bent, and typically canoe shaped (fig. 7-6); and microconidia, which are usually one-celled, ovoid or oblong, and borne singly or in chains. Macroconidia form more frequently when cultures art incubated under light. Biology the absence of host plants, most species of Fusarium remain dormant as thick-walled resting spores called chlamydospores, either in the soil or on decaying organic matter like dead roots. As a result, roots of diseased seedlings from previous crops are suspected as major sources of inoculum for new infections. The chlamydospores germinate when root exudates are present and when soil temperatures are warm. When conditions are favorable, the fungus grows over the root surface, penetrates the epidermis, and spreads through the cortex and xylem of infected roots, resulting in death and decay of these tissues. Control Prevention - Nursery site selection is a critical factor in avoiding disease losses. Heavy soils and sites that were once used to grow agricultural crops may have high levels of Fusarium. Avoid poorly drained soils with an underlying hardpan. Finally, areas of the nursery with a history of heavy losses should be used for transplants rather than for seedbeds. Observe strict sanitation. Do not pile culls on seedbeds, for example. Remove dead and infected seedlings before seedhed preparation. Cultural - If possible, sow in the fall, which normally results in less mortality than spring sowing. Use sawdust mulching and irrigation, which reduce the soil temperature and thus may be helpful in reducing the disease. In container nurseries, hardwood bark has been helpful in reducing the disease. Use a balanced fertilizer to avoid excess levels of nitrogen, which appears to increase the amount of disease; potassium, on the other hand, seems to reduce seedling losses. Selected References Bloomberg, W.J. 1973. Fusarium root rot of Douglas-fir seedlings. Phytopathology. 63: 337-341. Katan, J. 1980. Solar pasteurization of soils for disease control: status and prospects. Plant Disease. 64: 450-454. Smith, Richard S.. Jr. 1975. Fusarium root disease. In: Peterson, Glenn W.: Smith. Richard S., Jr., tech. coords. Forest nursery diseases in the United States. Agric. Handb. 470. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture: 9-10. Wright. E.; Harvey. G.M.; Bigelow, C.A. 1963. Tests to control fusarium root rot of ponderosa pine in the Pacific Northest. Tree Planters' Notes. 59: 15-20. |

Forest Pests: Insects, Diseases & Other Damage Agents |

|

|